This post is part of a longform project I’m serializing exclusively in my newsletter, Disruptor. It’s a follow-up to my first book, Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Built an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture, and it’s called Masters of Disruption: How the Gamer Generation Built the Future. To follow along, please subscribe to Disruptor and spread the word. Thanks!

In the annals of online history, Neopets, a pioneering world for virtual pets from the aughts, took important early steps in metaverse creation. Recently, it’s been back in the news. The New York Times wrote about fans who are still playing with their Neopets. And there was even an uproar around plans to create Neopet NFTs as part of a new project called the Neopets Metaverse.

As we look at the evolution of the metaverse, let’s revisit Neopets mania, which I chronicled for WIRED magazine. This story by me first appeared in WIRED as “The Neopets Addiction,” December 1, 2005.

Every day after school, 11-year-old Tyler Gagen hurries home down the country roads of Hastings, Minnesota, to play with Buddy. “He likes hot dogs and cake,” Tyler says of his pet. “I haven’t brought him to the grooming parlor yet, but I will. He gets the royal treatment!” Tyler also cares for a half-Siamese tomcat, Arctic, and two cocker spaniels, Packer and Patriot. Tyler likes Buddy but says he appreciates the dogs and cat a little more because “you can actually feel them and stuff.”

Buddy is a winged, wide-eyed baby dragon that lives in the online land of Neopia. Tyler “adopted” Buddy five months ago and personalized his color (green) and gender (male). Now he spends two hours a day at Neopets.com, shopping for Vonroo toys and Cornupepper soup to keep Buddy happy and healthy. With frequent exercise, he has pumped Buddy’s strength from “average” to “above average.” Clicking through the Flash-animated world, which is divided into theme park-style zones like Mystery Island and Terror Mountain, Tyler tries to accumulate NeoPoints, the local currency. So far he has earned 10,000 points by playing games (Wheel of Misfortune is one of his faves). When he gets another 10,000, he hopes to expand Buddy’s house or maybe relocate him to a more upscale zone like Spooky Woods.

“It’s the most insidious mind-fuck ever.”

Tyler heard about the Web site from a girl named Anna down the street. He initially dismissed Neopets as “little ponies and stuff,” but before long he had given up Grand Theft Auto for Faerie Paintbrushes. “Neopets is a lot wimpier,” Tyler says unapologetically, “but it’s fun.”

A generation agrees. Neopets has a staggering 25 million members worldwide. It has been translated into 10 languages and gets more than 2.2 billion pageviews per month. These dedicated Neopians spend an average of 6 hours and 15 minutes per month on the site. That makes Neopets the second-stickiest site on the Internet – ahead of Yahoo!, MSN, AOL, and eBay, according to Media Metrix. What’s more, its demographics are the stuff of marketers’ dreams: Four out of five Neopians are under age 18, and two out of five are under 13.

It’s these numbers that have captured everyone’s attention – Madison Avenue, Hollywood, and toy companies, all desperately trying to grab younger and younger audiences. The Neopets characters now appear as stuffed animals and action figures and on board games and trading cards. Warner Bros. is developing a Neopets feature film. A PlayStation 2 version hit the market in October, and a PSP version is due out next year. And then there’s perhaps the biggest deal of all: In June, Viacom – which owns CBS, MTV, Nickelodeon, and Paramount Pictures – bought Neopets for $160 million. “We want to be wherever kids are,” says Jeff Dunn, president of Nickelodeon, who took charge of the Neopets brand. “And there are plenty of kids at Neopets.”

For Viacom, the main draw is the site’s advertising model. In a world of TiVo, pop-up blockers, and satellite radio, where it keeps getting harder to reach people with ads, Neopets collapses the boundaries between content and commercials. Many zones in the vast make-believe world, like the Firefly Mobile Phone Zone, are sponsored by companies, and there are branded games like Nestlé Ice Cream Frozen Flights and Pepperidge Farms Goldfish Sandwich Snackers. Tyler likes to play McDonald’s: Meal Hunt, in which he searches for lost McNuggets. Jana Gagen, his mom, says they’ve been taking more trips to the real-world McDonald’s ever since Tyler started racking up NeoPoints in the restaurant’s online game. “We go to get the Neopets toys,” she says. The tie-in merchandise comes with Happy Meals.

Neopets calls its model “immersive advertising” and hypes it in a press kit as “an evolutionary step forward in the traditional marketing practice of product placement.”

That sends critics like Kalle Lasn, editor in chief of the advertising watchdog magazine Adbusters, reeling. “They’re encouraging kids to spend hours in front of the screen and at the same time recruiting them into consumer culture,” Lasn says. “It’s the most insidious mind-fuck ever.”

There’s a perfect Smurf-blue sky over Southern California on this July afternoon, and Neopets CEO Doug Dohring is preaching the Neopian gospel. “I always saw this as more than just an Internet company,” Dohring says. Dressed in a dark suit, the chummy 47-year-old chuckles heartily and frequently as we talk, and his hair becomes increasingly unkempt as he extols the virtues of his online pet sim. A shelf in the conference room at the company’s Los Angeles headquarters is crammed with Neopet plush toys, trading cards, and CD racks. A Warholian portrait of a Neopet hangs on the wall. The table is dominated by an enormous bowl of jelly beans with a soup ladle inside.

Dohring’s feeling particularly giddy today. He and a dozen executives have just returned from deep-sea fishing and volcano climbing on Maui. In May, two of his top guns received the Entertainment Marketer of the Year award from Advertising Age. And, having recently concluded the Viacom deal, he’s basking in a $160 million glow.

Down the hall, past the two human-size Neopets in the reception area, dozens of geeks in blue jeans and T-shirts keep Neopia churning from their tchotchke-lined cubicles. Running this Oz is a round-the-clock enterprise, requiring 110 staffers in LA and another 20 in Singapore. Translators post the latest Neopian news in 10 languages. Programmers code minigames. Artists draw shiny, happy mutant pets. Sketches of the two latest breeds of Neopets – the Hissi, a winged serpent, and the Ruki, a flying insect – cover the walls. New characters, games, locales, and prizes are added to the online world almost daily. This efficient Hollywood-style assembly line is a far cry from the scrappy UK startup launched in November 1999 by a young couple hoping to quit their day jobs. Adam Powell and Donna Williams, still together and still with the company, met while they were high school students in Surrey. Powell grew up bagging groceries and coding his own role-playing games; Williams rode horses and dabbled in sculpture. Powell had left college in Nottingham to start an online-advertising agency. But making banner ads, primarily for his dad’s hot water-bottle company, wasn’t very lucrative – or interesting.

The couple had a veritable zoo of real-life pets, including birds, guinea pigs, and a tempestuous cat named Oscar. Powell and Williams imagined a fantasy pet site so addictive that people would gladly suffer through ads to experience it. “We thought virtual pets was a good idea,” Powell says, “because people would get attached and keep coming back.”

Living on credit cards, Powell began coding the larval version of the Neopets site while Williams, an art student at the time, handled the graphic design. “We wanted unique characters,” Williams recalls, “something fantasy-based that could live in this weird, wonderful world.” There was just one problem, Powell says. “Donna couldn’t draw.”

The Neopets themselves were decidedly less cutesy than, say, Pokémon. But the characters were shot through with wry collegiate prankishness. There were references to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (the option to feed your pet a Pan Galactic George Slushie, for example). One of the creatures was simply a JPEG of bow-tied British game show host Bruce Forsyth. “We were just trying to amuse ourselves,” Powell says. “If people found it all funny, great.” People did. After posting on a few pet newsgroups, Powell and Williams watched site traffic double day after day.

By Christmas 1999, Powell and Williams were getting 600,000 pagevviews a day. But they were running out of money. They didn’t have much in common with market research magnate Doug Dohring, but he had plenty of cash and they shared a vision. “We all saw the potential for this to be huge,” Powell says.

Dohring brought two things to the company: expertise in market research and a deep commitment to the principles of Scientology. After college, he spent four years in Toledo working for the church in “counseling and communications.” In the writings of Scientology leader L. Ron Hubbard, Dohring discovered a business model that would later become the foundation of the Neopets operation. “He created a management technology that’s very powerful,” Dohring says. Hubbard’s companies follow a system of departmental organization called the Org Board, which he claimed was a refinement of one used by “an old Galactic civilization” that lasted 80 trillion years. Dohring is more concerned with down-to-earth prescriptions, like a corrections division to monitor the performance of other divisions. “It sounds like common sense,” he says. “But you’d be surprised. Most companies are missing that.”

Dohring first put these business principles into action in 1986, at age 28, when he started the Dohring Company. This market research firm soon became one of the largest in the US, a top provider of data to the automotive industry. The key to his success, he says, was paying attention not to the consumers who weren’t buying, but to the ones who were. “Research what you’re doing right,” he says.

The Dohring Company moved to the Web in the 1990s and soon was selling polling data from 1 million online consumers to corporate customers. Dohring also invested in the Web-based game developer Speedyclick, which he later sold for $50 million. But the biggest payoff came when a Speedyclick staffer told Dohring about a British couple struggling to maintain an offbeat, highly trafficked virtual-pet site.

Dohring was so impressed by Neopets that he convinced his management team to buy the company for what he calls “a significant sum” in January 2000. The investment was initially passive, but one Saturday Dohring called in his team to tell them he wanted a more active role.

“I realized we could have the best of both worlds,” he says.”We could use the Internet to create Neopets that would reach youth on a global scale, and then be taken into the real world. It was a Net-to-land strategy, the opposite of what everyone else was trying to do.” Neopets could become like Marvel comics for a new generation – spinning its core product off into endless additional mediums. “I never thought we could be bigger than Disney,” Dohring says, “but if we could create something like Disney – that would be phenomenal.”

Dohring brought along his previous company’s market research experts – and Hubbard-powered efficiency. They shunned the splashy ad campaigns other boom-era dotcoms used to build audiences, relying instead on Neopets’ devotees. “It’s all word of mouth,” says Lee Borth, Neopets’ COO. “It’s the school yard.” Dohring maintained the quirkiness of the original vision and has even retained the site’s “colourful” Britishisms. But he’s also made changes. “I ordinarily don’t show this to people,” he says, as he twiddles his laptop in the conference room, “but here you go.” A window opens on a large monitor nestled between the stuffed animals. It displays what might be called the Evolution of Bruce. On the left is the original Bruce, a bow-tied Neopet that was Williams’ tribute to Bruce Forsyth. On the right is Bruce as he appears today: a tiny blue penguin.

“He still has his bow tie, but that’s about all that’s similar,” Dohring says, admiring the art like a dad looking at his kid’s drawings. He says Powell and Williams didn’t care about using other people’s intellectual property. “One of the first hires I made was a general counsel. I said, ‘We need to own everything 100 percent. And if we can’t own it, remove it.'”

Dohring’s next move was to identify new ways to generate revenue. The result: immersive advertising, a phrase Neopets has trademarked.

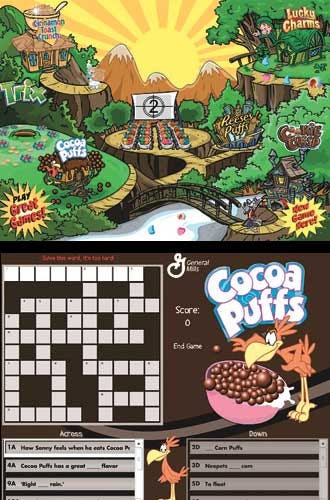

The idea is straightforward enough. For example, a link from Neopia Central, the site’s shopping district, takes members to a splash page for the Cereal Adventure zone. Dotting lush green hillsides are the homes of a half-dozen breakfast mascots, from the Trix rabbit to the Cocoa Puffs cuckoo. Clicking on Lucky the Leprechaun leads to a game called Lucky Charms: Shooting Stars!, in which kids navigate a series of marshmallow treats – hearts! moons! stars! – to earn NeoPoints.

Visitors can also surf into the Disney Theater, where they can buy their pets some popcorn (740 NeoPoints) and settle in to watch previews for Lilo & Stitch 2. And they can earn 300 NeoPoints by answering a market research survey linked from the homepage (questions like, When was your last visit to Wal-Mart, and Are you aware there’s a new Power Rangers DVD?). Kate Parker, an 11-year-old Neopian from Mason, Ohio, likes to play the Limited Too: Mix & Match game, which lets her combine images of actual clothing sold at the tween boutique. “It’s got good advertising and fun colors,” she says, “and shows you things you might want to buy in real life.”

The roster of clients who have set up shop inside the land of Neopia runs from Atari and DreamWorks to Frito-Lay and Lego. While passive product placement has become standard in TV and film, the Neopets approach emphasizes interaction and integration. Neopians can even win virtual trophies featuring Bubble Yum and SweeTarts, and display them for other players.

This seamless interweaving of marketing and entertainment is an advertiser’s dream come true. “There’s nothing on the Net delivering an experience like Neopets,” says David Card, a senior analyst for Jupiter Research. “Kids aren’t being harangued, and parents think it’s safe.”

It’s precisely this kind of environment that proved irresistible to Viacom, which is on a mission of corporate reinvention through what chair Sumner Redstone calls “an accelerated expansion into new and emerging platforms.” Dohring now answers to Jeff Dunn, president of Nickelodeon. Dunn says that Neopets is a great complement to Nick.com and other kid-friendly Viacom portals. “We couldn’t help notice that there was this site that had an enormous number of kids,” Dunn says. “It’s quicker and easier and more effective to buy Neopets than to start something incremental ourselves.”

Of course, what attracted Viacom to Neopets is exactly what makes children’s advocates and media critics bristle. “It’s clearly an effort to plant brand names in the minds of children,” says James McNeal, professor emeritus of marketing at Texas A&M University and author of The Kids Market: Myths and Realities. “It is not until around 8 years old that they can mentally defend against a persuasive sales message if they wish to.” Neopets reports that half a million of its users are under age 8.

Susan Linn, associate director of the Media Center for Children at Judge Baker Children’s Center, agrees. “When childhood obesity is a major public health problem, what moral, ethical, or social justification is there for having kids earn points by watching commercials for sugar cereals?”

Dohring turns his palms to the ceiling and shrugs. “You’re never going to please everybody,” he says. He insists there’s “nothing subliminal” at work and that no one is forcing kids to play the ad-driven games. “This wasn’t done, like, Oh, let’s make this healthy. We just put all kinds of things on the site, and users will migrate toward things that interest them.” The immersive ads make up a small fraction of site content, he says, and are clearly labeled. This is true: There’s small print at the bottom of the Neopia Central page that reads, “This page contains paid advertisements.” But it doesn’t identify where and how those ads appear; young children may have trouble distinguishing them from other content on the site.

Occasionally, Neopets does give in to criticism. After parents’ groups raised an outcry over kids gambling for NeoPoints, the company limited access to its roulette, blackjack, and slots to players 13 and over (a cutoff many find ludicrous and arbitrary). But Dohring didn’t respond to outcries of Neopians who lost their shirts on the Neodaq, a stock market in which all members can invest their NeoPoints. “Around the time of the Enron scandal, we bankrupted three of those companies just for the hell of it,” he says. The Neopians weren’t amused. “They were saying, ‘This is no fair!'” he recalls with a laugh. “But, hey, stuff happens in the world.”

At 51, Jane Ash, a market research director in Manhattan, is outside the Neopet demographic (3 percent of users are over 30). “People have the perception that this is a kids’ site,” she says. “But I’m hooked.”

While preteens like Tyler Gagen accessorize their pets and clash in the Battle Dome, Ash spends a couple of hours a day obsessively collecting virtual tchotchkes. “I’m not a big shopper in real life,” she says in a thick New York accent. “You get hot and sweaty going store to store.” In Neopia, she’s amassed an impressive 16,000 Neopet prizes, which she displays in a gallery within Neopia. Her winnings include a Meepit Lamp (a furry pink light with an eyeball poking through the shade) and the H400 Helmet (an ice-blasting space weapon).

How does Neopets keep people coming back and attract new members to replace the kids – and adults – who outgrow it? The answer is in Ash and her Meepit Lamp. “If the content is good, users will connect with it,” Dohring says. “Look at the Simpsons. Look at SpongeBob. We’re a content-driven company creating an ever-expanding world by adding to it in a controlled manner.”

But controlling the content on the stickiest kids’ site on earth is an increasingly sticky matter. With a goal, as Dohring puts it, of creating “a safe haven for kids,” Neopets is constantly battling crooked players and dirty words. And the company doesn’t always win. “There’s an amazing number of people whose favorite thing is to ruin Neopets,” Ash says.

In June, Ash was among the Neopian shoppers who noticed an overabundance of Faerie Paintbrushes, a tool that recolors pets. Though Neopets forbids real-money transactions for game items (and eBay blocks auctions of Neopian goods), the virtual economy, including the Neodaq, is an important feature of online life. Hackers found a way to duplicate the Faerie brushes, and that sent the market into a tailspin. Even worse, many kids unknowingly fill out hacked login screens, only to find their accounts phished of hard-earned NeoPoints.

While Neopets fights off the hackers, it’s focusing on the equally important task of ensuring the site is smut free. In an online world, that’s more complicated than banning the seven dirty words. Neopets bars kids under 13 from using the messaging features, and it has created a proprietary language filter to root out profanity in every language supported. “We block over 1,000 versions of the F-word,” Dohring boasts. “If someone types, ‘I’m hot and sexy and 14,’ we change the word sexy to stupid.”

But with no credit card numbers to verify identity, nothing prevents an 8-year-old from registering as an 18-year-old to post instant messages. And although they can’t select a username like Phuckhead, because it’s blocked, they could choose Childmolester – if it weren’t already taken.

It’s the end of another day in reality, but the sun never sets on Neopia. The Cocoa Puffs birdie is cuckooing by its cottage. Players face off in the Battle Dome. Virtual SweeTarts and McDonald’s hot fudge sundaes are on display in users’ galleries.

In Huntsville, Alabama, 4-year-old Megan Fanning and her 54-year-old grandmother, Susan Wilson, are tending to their Neopets. Wilson, recently disabled by osteoarthritis, spends hours a day volunteering with DL’s Adoption Agency, a Web site that takes in abandoned Neopets and places them with new owners. “The only thing we require is a good application so we know they’re going to a good home,” says Wilson. “Even though these are just pixels, some of us get a little nutty about the pets.”

The problem every popular kids’ site faces is that users outgrow it and move on. But as long as a grandmother and granddaughter can play the game together – and match new users with old Neopets – the future of Neopia looks promising.”There are days when I think, you know, What am I doing?” says Wilson. “There’s life. There’s my family. There’s outside. Then my granddaughter runs up and says, ‘Let’s feed my Neopet!'”

And they’re back inside.