This post is part of a longform project I’m serializing exclusively in my newsletter, Disruptor. It’s a follow-up to my first book, Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Built an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture, and it’s called Masters of Disruption: How the Gamer Generation Built the Future. To follow along, please subscribe to Disruptor and spread the word. Thanks!

This article originally appeared in IEEE Spectrum as “From Bricks to Bits,” June 2010.

“There’s a darkling, dude! Come on!” It’s after school in Louisville, Colo., and two boys are playing just like generations of kids before them—with Lego bricks. As their little yellow LEGO guys battle some evil monsters called the Darklings, the boy in the blue shirt yelps to his friend, “You gotta start building a bridge now! Hurry!” A bridge takes shape as interlocking Lego bricks snap together.

But this is no ordinary playdate. The boys are sitting in a windowless room behind a two-way mirror. Cameras monitor their every move, and a scruffy technician taps notes into a laptop. The biggest difference, though, is the LEGO blocks themselves. They aren’t made of plastic. They’re made of pixels.

The boys are play-testing LEGO Universe, an online computer game due out in October. Ten years in the making, the game is being created here at a company called NetDevil, with supervision from the LEGO Group. It’s a children’s product, but it’s also serious business. LEGO Universe marks the legendary company’s first foray into massively multiplayer gaming, and for the iconic building-block maker, it’s a major gamble. With the game, the creators are aiming to pull off three incredibly difficult feats: translating the creative, distinctly tactile LEGO experience into a virtual arena; creating an online environment that’s both kid-friendly and kid-safe; and opening up a new market for the US $2 billion toy company.

And because this is an international project and brand, addressing these issues is a global challenge. On launch, subscriptions will be available to over 20 countries from Austria to the United States. Success for this project—estimated to cost over $10 million to create, though the Danish company does not make the budget publicly available—is by no means assured. The company has had occasional troubles before, such as trying to create its LEGO theme parks.

Most massively multiplayer games cater to an older crowd, where norms of behavior need not be strictly enforced. But LEGO Universe seeks to capture the grade school set and the estimated $20 billion children’s game market. It’s one thing to unleash bawdy mayhem in a fantasy game like EverQuest and quite another to nurture a virtual play space where kids can be kids—and not fall prey to predators or bullies or other unwelcome Internet lurkers. So with LEGO Universe, the company’s reputation as one of the most venerated and parent-friendly toy brands is at stake.

In addition, LEGO must stay faithful to its meticulous engineering. It can’t afford to disappoint users looking for the familiar interplay of studded plastic pieces that families have been clicking together for generations. Everything built in the game must be buildable in real life.

But unlike traditional LEGO play, the online version will offer unprecedented opportunities for players to share and interact. The sprawling LEGO fantasyland will be able to support more than half a million “brick heads” from around the world. Each player will start by assembling a personal LEGO miniature figure to serve as his or her avatar. Players can then venture into the live LEGO Universe, where forces of chaos and destruction—monsters such as the Darklings—threaten to destroy the Land of Imagination.

As players explore brightly colored lands such as the Avant Gardens and the Gnarled Forest, they’ll get to build rocket ships and skyscrapers and animals and whatever else they can imagine. With over 2000 types of pieces in 26 colors, the variations are seemingly endless. Players will also receive their own property, which they can populate with their constructions. Using the simple icon-based programming that LEGO developed for its Mindstorms robotics program, players can even animate their creations—a rocket ship that flies or a Ming dynasty vase that rotates when visitors get close. And of course, online virtual creations can be made physical—for a price. Using a service called Design by Me, a player can have a kit of physical blocks shipped directly from the LEGO factory and then rebuild the virtual LEGO construction for real.

“It’s definitely going to be a challenge,” says Michael Gartenberg, a partner with Altimeter, a technology research firm based in New York City. “They want and need to protect their brand; they need to make sure this experience will be kid-friendly.” But given the popularity of Lego, there’s little room for error. “They’re taking a fairly big risk and they have to get it right immediately,” Gartenberg says. “It’s not something they can check out and hopefully have it work and work out bugs.” In the end, though, it all comes down to winning over kids like the two boys behind the two-way mirror.

In the beginning, there was the brick. And that universally recognized building block remains at the core of LEGO Universe. Of course, an online brick has no substance; you can’t hold it in your hand or feel the satisfying snap of connecting two blocks together. Beyond replicating that sound, LEGO doesn’t attempt the impossible. Instead, the game puts all its emphasis on creating an authentic simulation of the building blocks themselves. “We couldn’t begin work on this game until we figured out how to make a virtual brick,” says Ronny Scherer, studio director of Lego Universe.

The brick has been through transformations before. When Danish carpenter Ole Kirk Christiansen began making toys in 1932, they were all made of wood. He called his company LEGO after the Danish phrase for “play well,” leg godt. With the adoption of injection molding machines in the mid-1940s, Christiansen and his son Godfred realized kids could play better with cellulose acetate, and they created plastic bricks that could be connected. The company began churning out brightly colored “automatic binding bricks,” later made from sturdier acrylonitrile butadiene styrene plastic, which is used to this day.

LEGO has often enhanced the play experience with new technologies. LEGO Mindstorms brought the bricks to life electromechanically and has hooked millions of kids on robotics. Lego video games, including LEGO Indiana Jones and LEGO Rock Band, are now mainstays on home gaming consoles. In 2004, LEGO introduced its Digital Designer software, a free program that lets a player design LEGO models on-screen.

LEGO began exploring the idea of a massively multiplayer online game in 1999, but prospective developers repeatedly told the company that there was no way to digitally replicate the bricks—and all their studs and crannies—with the necessary fidelity. In 2006, LEGO finally awarded the project to NetDevil, an online-game company founded in 1997.

NetDevil was known among game aficionados for the nimble and realistic physics of games like Jumpgate, Auto Assault, and Warmonger, but it had never done a children’s game before. NetDevil programmers were initially stumped when they heard that players would likely be using graphics cards that were several generations behind the times. “Kids tend to play on older computers,” explains Ryan Seabury, NetDevil’s creative director. “They get the hand-me-downs.” How on earth would they be able to render an entire world of bricks for players using graphics cards built in 2003?

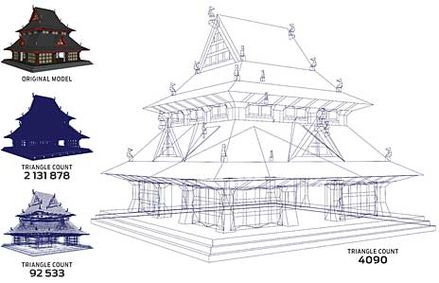

Digital objects aren’t solid; they consist of numerous flat polygons connected into a 3-D shape. A simple-looking object isn’t necessarily simple to render on screen. While an avatar in an online game such as World of Warcraft might consist of 2500 triangles, a detailed rendering of a one-centimeter-square Lego brick can have over 250 000, thanks to the perfectly round studs and other fine details.

“A digital brick has to look like a real brick,” says NetDevil technical director, Eric Urdang, holding up a bright red rectangular block. “It has to have that certain sheen and imperfections.”

NetDevil developers figured that they could have a maximum of 500 000 polygons on screen before the frame rate slowed and animations began to look jerky. When programmers initially built a pirate ship, they found that it alone contained 430 000 polygons. “The more polygons, the less you can do,” says Urdang, “so we had to find smart ways to make this efficient.”

NetDevil spent two years experimenting with ways to decrease the polygon counts. Techniques such as bump mapping—in which 3-D textures are simulated with 2-D images—proved too unwieldy for the underpowered graphics processors they were targeting. Instead, the solution came from examining the real-life bricks. When LEGO blocks are snapped together, the interlocking studs disappear. So rather than draw every unseen portion of the brick, the computer could be instructed to draw only the visible parts. “There’s lots of polygons you can throw away,” says Urdang.

Though it sounds simple enough, the implementation was anything but. Urdang and his team of 40 engineers applied a technique called hidden surface removal, which involved going into the 3-D model of each LEGO object and manually erasing the hidden portions. The team then spent another two years automating the process, until what had taken hours by hand could be done in seconds. That 430 000-polygon pirate ship got squeezed down to just 13 000 in a fraction of a second.

One day last summer at NetDevil, the LEGO Universe team gathered around the table in the company’s sprawling conference room for a project code-named Naughty Duck. LEGO ducks are an inside joke at the company. Upon arrival at the Danish headquarters, new employees are given the fowl test, which involves building a duck out of just six LEGO pieces. The NetDevil challenge had a twist: Using the same six duck pieces, team members were asked to create the most obscene object imaginable. “We got a lot of phalluses,” says Seabury.

The experiment was no laughing matter. LEGO Universe, like World of Warcraft or EverQuest, isn’t just a product; it’s a social space. While Lego’s core demographic is 8- to 12-year-olds, some of the most ardent fans are adults. But as cautious parents everywhere know, allowing unknown adults to mix with young kids in an unsupervised, unfettered environment is simply not wise. That’s as true online as it is in the real world. Most online worlds for kids such as Webkinz or Club Penguin address this issue by granting users very limited freedom to express themselves. But as I’m frequently told throughout my visit, LEGO is all about creativity, and the company wants to foster that same spirit online. At the same time, says Mark Hansen, senior director of LEGO Universe, “Children’s safety is high priority. We don’t want to put kids at risk.”

So how do you balance creativity with safety? Lego is taking several approaches. First, it’s charging for subscriptions to LEGO Universe, which creates inherent accountability, because each account can be traced back to an individual. That alone isn’t adequate to rein in the riffraff; if a player subscribes using a gift card or fills out the personal information incorrectly, the account tells Lego very little.

The second safety backstop is having online moderators. Though LEGO Universe hopes eventually to automate the moderation process, for now it will be conducted by a designated team of employees around the world. At any given time, roughly 100 LEGO Universe moderators—roughly one for every 500 players—situated around the globe will be overseeing the game.

It turns out that safety is as much an engineering challenge as one of enforcement. “Positive social behavior can be engineered into the game,” Seabury says. NetDevil and LEGO thought long and hard about how to implement free-form building in the online game. They certainly didn’t want to repeat the experience of Electronic Arts, which struggled to keep up with the provocatively shaped creatures that users created in its online game Spore (which earned the nickname Sporn).

Hence the Naughty Duck test. At various points in LEGO Universe, players will encounter a similarly random pile of bricks and be challenged to arrange them into something useful—say, an elevator or a bridge. The test is called a showcase. By limiting each showcase to a small number of bricks, LEGO hopes to limit abuses to the vaguely suggestive. Also, any new showcase creation is viewable at first only by its creator. If a player is proud of her handiwork and wants to show it off to others, she can submit it to LEGO’s moderators for approval. Things that LEGO disapproves of extend well beyond phalluses; they also include religious symbols such as crosses and six-pointed stars.

The company is now looking at how to handle users who create letters that can be linked together to spell profane words in a variety of languages. It’s possible that LEGO Universe players will not be allowed to make shapes representing their ABCs, at least not in public. But on their own property, which requires special access, players will be freer to create (though even that content will still be subject to moderation). And when two players “friend” each other, the content they share becomes trusted and doesn’t necessarily get the same level of moderator scrutiny.

It’s not just LEGO constructions that must be moderated. LEGO Universe also has chat rooms for its players. Other virtual worlds for kids limit conversation to preselected chat phrases like “This is fun!” or “What’s up?” LEGO didn’t want to be quite that restrictive. Instead, a user can compose messages from any of the roughly 2000 acceptable words on a “white list.” Each language has its own list. Here, obscenity is not the chief concern; bullying and predatory behavior are. At the moment, for example, Lego will not allow numeric characters in messages, to try to prevent users from giving out addresses and phone numbers. Moderators will be checking in as well, which means that LEGO needs employees who are proficient in numerous languages.

The company will also employ a behavior rating system for the game, using algorithms that will assign each player a “goodness score” (based on such achievements as building and sharing well-made objects) and a “badness score” (triggered by obscenity and bullying). “If a player does inappropriate activity, they’ll be moderated more often,” says Scherer.

If it all sounds impossible to control, LEGO admits that on a certain level, it is. The easy answer would be simply to crack down—limit the chat, limit the blocks, limit players’ ability to share. But that would go against the company’s philosophy. “The platform is to inspire creativity,” says Seabury, “and creativity doesn’t come if you block everyone’s ability to communicate.”

Back at NetDevil, the two play-testing boys head out, and a girl and her mom arrive for their turn. In the lobby, the girl gazes in awe at the life-size LEGO figurines dressed up in holiday outfits, standing on clouds of puffy white cotton amid LEGO reindeer.

The mother and daughter stop to peek in on a guy assembling a giant Star Wars Millennium Falcon out of LEGO bricks. He’s one of several full-time employees assigned to test-build objects in the game to make sure they can be constructed in real life. Behind him are rows and rows of multicolored tubs of LEGO pieces. With 10 million pieces in house, NetDevil has one of the top five LEGO collections in the world. “Wow,” says the girl, eyes widening.

It’s exactly that sense of wonder that LEGO hopes to foster and protect online—despite skeptics who question just how effective virtual LEGO can be. “The computer game misses a very important component of play for a child: human interaction,” says Mona Delahooke, a child psychology expert with the American Psychological Association. “Building LEGO creations with a parent or friend involves social communication—commenting on each other’s work, sharing nonverbally by looking and smiling, giving and taking feedback, and so on. My concern with computer LEGO is that it takes away the human interface—which is play, children’s natural language of learning.”

But even as its creators iron out the final technical and security hurdles, LEGO Universe is already set to grow. It will launch with six thematic worlds, with two to four new expansions each year. Ultimately, the goal is to break down the fourth wall between plastic and pixels, so that someone can buy a box of LEGO bricks in a store and play with them online or off. “The design of LEGO Universe is that all things LEGO past, present, and future can fit into this world,” says Scherer.

This post is part of a longform project I’m serializing exclusively in my newsletter, Disruptor. It’s a follow-up to my first book, Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Built an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture, and it’s called Masters of Disruption: How the Gamer Generation Built the Future. To follow along, please subscribe to Disruptor and spread the word. Thanks!