Masters of Disruption: How the Gamer Generation Built the Future [2]

"Minecraft and Fortnite are closer to the metaverse than anything Facebook has built, or frankly, is likely to build,” John Carmack tells me.

This post is part of a new “book” I’m serializing exclusively in my newsletter, Disruptor. It’s a follow-up to my first book, Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Built an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture, and it’s called Masters of Disruption: How the Gamer Generation Built the Future. To follow along, please subscribe to Disruptor. Thanks!

John Carmack, one of the most influential programmers of our time, isn’t much of a sentimentalist. But in his home office in Dallas, he displays posters of his babies: the seminal videogame franchises, Wolfenstein-3D, Doom, and Quake. “Someone made them on Kickstarter,” he tells me during a recent Zoom, “I thought that was pretty cool.”

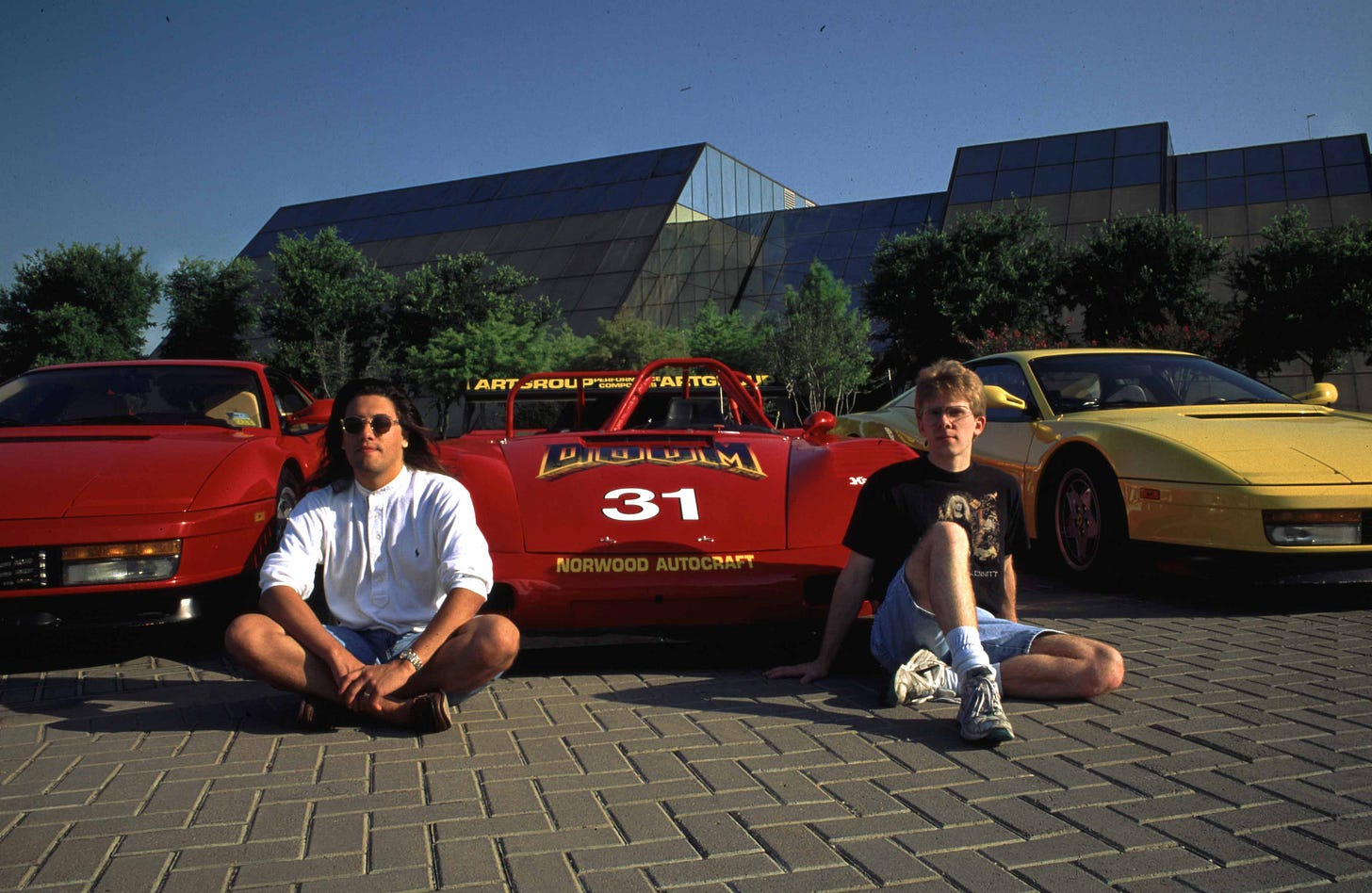

During his years as the lead coder of id Software, the company he co-founded in 1991, Carmack helped pioneer the $150 billion dollar culture and industry of modern gaming. As I chronicle in Masters of Doom, id Software established the first person shooter genre that made Fortnite, Call of Duty, Halo, and other hits possible.

Carmack’s technological breakthroughs in multiplayer online gaming paved the way for esports. His and co-founder John Romero’s commitment to the Hacker Ethic - such as giving away software tools that let players modify games - empowered a generation of geeks to create companies of their own, from Valve to Reddit.

“The idea a few friends could get together in a house and start building something the world had never seen before – having a lot of fun in the process -- got me hooked,” Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian blogged. Carmack’s innovations in 3-D graphics inspired the launch of Oculus, Facebook’s virtual reality subsidiary. He left id Software in 2013 to become the company’s chief technology officer.

These days, the man who once made high-powered rockets for fun (and still trades notes with his friend, Elon Musk) is pursuing his greatest challenge yet: artificial general intelligence or AGI, a yet nonexistent form of digital agent that can observe and learn like the human mind. (I’ll be exploring these and other of Carmack’s pursuits in future posts).

“There may be a shortcut to the future. That is very much what I've always been about.”

Carmack stepped back from Facebook two years ago to become a consulting CTO, so that he could devote himself full-time to the mission. “I have sometimes wondered how I would fare with a problem where the solution really isn’t in sight,” the 51-year-old wrote on Facebook at the time, “I decided that I should give it a try before I get too old.” He now spends his days at his home working alone as what he calls a “Victorian Gentleman Scientist” of AGI.

Though there’s a decent chance AGI will arrive in 30 years, Carmack tells me, he thinks he might be able to create it sooner. “The conventional approach may yet turn out to work,” he says, “Given enough time and resources, it almost certainly will, but there may be a shortcut to the future. And that is very much what I've always been about.”

In a lot of ways, this is the same Carmack I remember from our dozens of hours of interviews 20 years ago 🤦♂️ for Masters of Doom. He’s still zipping around in a high-performance car (no longer a Turbo-charged Ferrari, but a Tesla P100D because “internal combustion just seems so antiquated now,” he says), and still building the fast track to tomorrow.

Yet there’s one increasingly popular road to the future he’s not keen on taking: the metaverse. Coined by Neal Stephenson in his influential 1992 sci-fi novel, Snow Crash, the metaverse describes a virtual world we inhabit together online. Like the Holodeck from Star Trek: The Next Generation, the metaverse became a holy grail for a nascent generation of gamers and geeks, including Carmack.

As I write in Masters of Doom, Carmack proposed building a metaverse in 2000, while at id Software. “We can have a lot of the 3-D web environment that people always are thinking about and wishing about,” he told his co-founders, “we can do it now.” But with the only partner who shared his vision, John Romero, pushed out of the company, Carmack’s plan fizzled.

“I have been fighting hard the entire time at Oculus to forestall any attempts to be doing Metaverses.”

Venture capitalists and geeks have been dreaming of the metaverse ever since. Today, the proliferation of enabling technologies - augmented reality, virtual reality, cryptocurrency, blockchain, and nonfungible tokens - has sent the biggest players racing to finally bring it to life.

In November, Walt Disney chief technology officer Tilak Mandadi described building a Disneyland "theme park metaverse…a shared magical world created by the convergence of virtually enhanced physical reality and physically persistent virtual space. In January, David Baszucki, CEO of Roblox, a online entertainment company, dubbed his group the "shepherds of the metaverse.” Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella spoke of creating a "enterprise metaverse” in July.

But by far the biggest declaration came from Carmack’s old boss level leader at Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg.

In June, Zuckerberg set off the Nerd Siren when he told his company that “our overarching goal across all of [Facebook’s] initiatives is to help bring the metaverse to life.” And, further, “I think we will effectively transition from people seeing us as primarily being a social media company to being a metaverse company,” he said.

But there’s one key person who is decidedly not down with the plan: the wizard of Oculus who made Zuck’s VR magic possible in the first place. “I have been fighting hard the entire time at Oculus to forestall any attempts to be doing metaverses,” Carmack tells me.

“The metaverse is a honeypot trap for architecture astronauts,” he goes on, “There is a whole class of programmers that just salivate at the idea of designing the architecture for the metaverse. But, more and more, I find that those types of initiatives are just not the ones that lead to productive value at the end.”

Instead, he says, game developers such as Mojang Studios, creators of Minecraft, and Epic Games, makers of Fortnite, are better positioned to realize this goal. Rather than setting out to create the framework of the metaverse, those companies focused on making compelling worlds worth visiting. “They started off with the idea of being an awesome, entertaining experience,” he says, “They were fun and value first, architecture second.”

“Minecraft and Fortnite are closer to the metaverse than anything Facebook has built, or frankly, is likely to build,” he tells me, “unless we wind up getting really lucky.”

This post is part of a longform project I’m serializing exclusively in my newsletter, Disruptor. It’s a follow-up to my first book, Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Built an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture, and it’s called Masters of Disruption: How the Gamer Generation Built the Future. To follow along, please subscribe to Disruptor and spread the word. Thanks!