This is the uncut, unedited version of my Rolling Stone story, The Face of Facebook, published April 6, 2006.

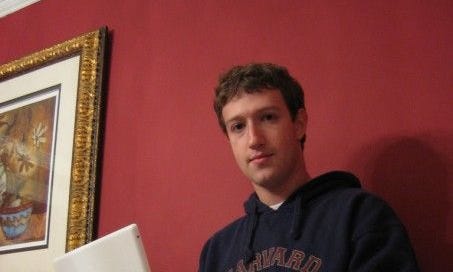

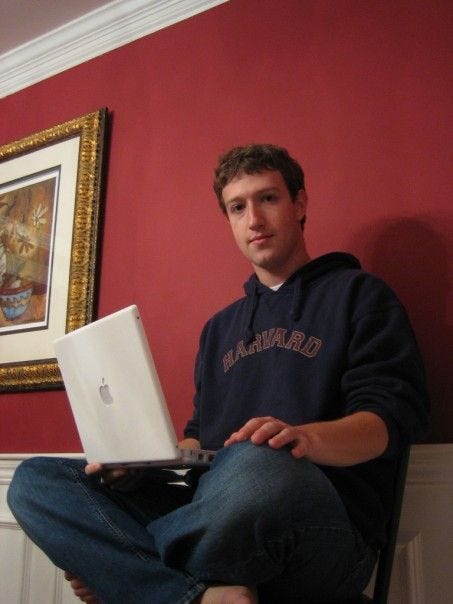

It’s late December 2005 in Palo Alto, California, but Silicon Valley’s newest wunderkind isn’t feeling the holiday glee. Upstairs in a busy loft decorated with Christmas lights and Family Guy posters, Mark Zuckerberg, a slight and bushy-haired 21-year-old, ambles from an elevator followed by his business partner and former Harvard roommate, Dustin Moskovitz, who’s riding a Razor scooter.

“You want to ask us some questions about sexual harassment?” Zuckerberg says wryly, as he flops into a chair and kicks off his worn Adidas sandals. Moskovitz brandishes a fistful of papers with an impish grin. The two have just left a lengthy seminar on the subject, a requirement for doing business here and small price for being the internet’s next big thing.

Zuckerberg is the creator of Facebook.com, a website that’s sweeping colleges and radically transforming student life. Facebook is an online student directory. Members upload their photos and bios for free, then search and link up with each other’s. You don’t ask for someone’s cell anymore, you Facebook them. “We’ve effectively removed the need to get someone’s phone number,” Zuckerberg tells me, proudly.

What makes Facebook unique from online communities such as Friendster and MySpace, is that it’s exclusively for academia. If you don’t have a “.edu” university email address, you can’t get on – which is just how students like it, thanks. Eleven million people from over 2000 universities and 22,000 high schools now use the site. Another 10 – 20,000 new ones join every day. As of November, Media Metrix ranks it as the 7th most viewed site on the Net.

“I think Mark’s amoral. We got our hearts ripped out.”

At the heart of the phenomenon is Zuckerberg, a precocious coder who dropped out of Harvard recently to run what Fortune dubs “the most buzzed-about company in Silicon Valley this side of Google.” With a company valued over $100 million, Zuckerberg recently secured $12.5 million in venture capital, though he refuses to sell out yet. “We’re having too much fun,” he tells me with a grin.

But his boyish posturing belies adult battles: one against school administrations, who are exploiting the network to bust students for everything from underage drinking to criticizing campus officials, and another against a trio of scorned Harvard classmates who have filed a federal lawsuit that Zuckerberg stole their idea outright.

“There’s a sense at Harvard that students will be forthright with each other,” says Cameron Winklevoss, a champion rower who, along with his twin brother and a friend, are the plaintiffs. “But I think Mark’s amoral,” he says, “We got our hearts ripped out.”

Zuckerberg denies the charge, and is countersuing for defamation of character. Now this kid who counts Weezer and hacker Justin Frankel among his heroes, is struggling to keep it all together, without growing up too fast. “I just want to build cool stuff,” he says, furrowing his brow, “and not let anything get in the way.”

One measure of a great Internet phenomenon is whether it becomes a verb. And, like Google, IM, and Mapquest before it, Facebook is making that rarefied leap.

The site, which Zuckerberg launched when he was a 19-year-old sophomore as a Harvard-only service in February 2004, serves a primal, but previously unfulfilled need: helping students keep track of each other. It draws its name and inspiration from the print “face book” directories that schools publish at the beginning of each academic year. Back in the 20th century, you’d arrive at school, pick up a face book, and thumb through the dorky headshots of your mysterious new classmates. But in the wired new world of surfing, texting, emailing, and IM’ing, that’s as sluggishly lame as waiting for the radio to play your favorite song.

Zuckerberg’s answer is the face book reloaded, designed by and for the Generation Xbox mind. Using the email address they receive when signing up for school, students register on the site at no cost and create a detailed profile (dorm, major, favorite TV shows, relationship status, etc.) for others to see. Once up, they surf around and – in what’s become another new verb – “friend” each other, which links up their profiles and creates what some have called a social network.

The title on Zuckerberg’s business card is “I’m CEO…bitch.” He tells me, “I’m a little more careful now about who I hand them too.”

Ordinarily when joining an online community, the profile creation step is when people feel a Darwinian need to bullshit. My name is Thor Steelcrotch, millionaire, and this picture is me, not a model I right-clicked from Abercrombie & Fitch. Facebook notably cuts through the crap because members must use, confirm, and display their real campus email addresses; as a result, there’s inherent social pressure to be who you are. You might actually run into these people in real-life, after all, so you’re less inclined to front. As Zuckerberg tells me, “The unique thing about Facebook is that it’s true.”

Ostensibly this gives the site academic potential, and, as Zuckerberg strains to note, people are indeed using it for study groups and carpools. But without the cloak of anonymity, many on Facebook are careening, sometimes wildly, in the opposite direction. These are the spawn of the Real World nation, after all, and Facebook is where they let it all hangout. Surfing the site feels like wandering through a giant dorm where every door’s wide open and a kid’s swilling Jack Daniels inside.

Photo of me passed out in vomit? Upload! Availability for three-ways? Noted! Twenty years from now, a presidential candidate will have to answer to something posted on Facebook. All this, plus students are listing their cell phone numbers and even class schedules too. The skeptics who call it a “stalker’s handbook” aren’t kidding.

Like Napster, violent video games, rock music, and every other seemingly dangerous facet of youth culture before it, Facebook is gathering plenty of controversy. Given the abundant binging and purging on the site, schools are actively using the site to bust students for assorted crimes. Pennsylvania State used a photo on the site to identify kids who rushed a football field. Schools including University of California at Santa Barbara and Northern Kentucky University have pursued disciplinary actions against underage students who are shown drinking in photos on Facebook pages.

At Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, just naming a Facebook group “Wasted” was enough to bring three students under investigation. Andy Wilson, assistant dean of students at Emory, says his staff doesn’t make a habit of surfing the site for violations, but won’t hesitate to put it to use. “If students are making an issue out of themselves [on Facebook],” he says, “we’ll investigate it.”

In photos online, of course, it’s impossible to tell separate the Red Bull from the vodka, and students say their being unjustly accused. Laura Steen, a junior at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina, had to pay a $50 fine and write a paper on alcohol abuse after her residence hall advisor saw a picture of her hoisting an empty shot glass. “I wasn’t even drinking,” claims Steen, who says she has since deleted every photo from her Facebook profile. “Anything can be taken out of context,” she says.

But it’s not just Animal House antics that are raising red flags, it’s speech. Private colleges, which fall outside constitutional protection for freedom of speech, have been enforcing their codes of conduct over Facebook, and other student blogs, in increasingly McCarthyesque fashion.

At Marquette University in October, a 22-year-old dental student got suspended after blogging about a professor whom he called “a cockmaster of a teacher.” In Boston the same month, Cameron Walker, the 20-year-old sophomore and student government president of Fisher College in Boston, Massachusetts, was expelled, along with one other student, after starting a Facebook group to rally against a campus cop who had become notorious for harassing students.

When his buddy jokes about facebooking hot Harvard girls, Zuckerberg awkwardly smacks him in the arm. “Dude, we just got out of a sexual harassment seminar,” he says.

“Either we get a petition going [we need at least 500 signatures],” Walker blogged, “or we try and set him up…anyone willing to get arrested?" Walker also called him a “douche bag” and wrote that the cop “needs to be eliminated.” When the administration learned of the Facebook entry from another student, Walker was called into a meeting with the Fisher College dean of students, chief of police, and school president, Dr. Charles C. Perkins, whom he claims called him “a fucking evil spirit” and told him he’d be asking “do you want fries with that?” for the rest of his life.

John McLaughlin, Fisher College chief of police and spokesperson, says Walker’s conspiratorial language violated the campus computer policy, and merited giving him the boot. “I’m a big believer in the first amendment,” McLaughlin says, “but as a private institution we have the ability to decide what discipline is appropriate...We’re reacting and being proactive.”

Sarah Wunsch of the American Civil Liberties Union, however, is concerned that the reactionary uproar over Facebook could have a chilling effect. “Even private colleges are supposed to be places where students can engage heated debate,” she says. Zuckerberg agrees, and he speaks from experience. He’s from Harvard, where Facebook was wrought in dissent.

There are two boxes of business cards on Mark Zuckerberg’s desk. One reads, “CEO,” and the other, ‘I’m CEO…Bitch.” As he flips through the dozens of new emails on his laptop, Zuckerberg explains that he’s fazing out the latter after inadvertently handing one to a reporter and seeing it wind up in print. “I’m a little more careful now about who I hand them too,” he says.

While Silicon Valley has seen its share of whiz kids, Zuckerberg is so young, he’s larval. He has ruddy just-played-in-the-snow cheeks, and is visibly accommodating to his new multimillion dollar role. When his buddy Moskovitz makes a crack about facebooking hot Harvard girls, Zuckerberg awkwardly smacks him in the arm. “Dude, we just got out of a sexual harassment seminar,” he says, seriously.

“Mark likes to get photographed in t-shirts that say ‘my Mom thinks I’m cool.’ But he knows exactly what he’s doing. He’s shrewd.”

The ironic thing about being at the heart of a youth culture phenomenon, whether your Kurt Cobain or the Olsen Twins, is that it forces you to grow up fast. By occupying the white hot overlay of digital and student culture, few have had their youth chastened like Zuckerberg. But the former Harvard classmates who have launched the Geek Wars against him, insist his barefoot pose is just that. “Mark likes to be all casual and get photographed in t-shirts that say ‘my Mom thinks I’m cool,” 23-year-old plaintiff Divya Narendra tells me, “but he knows exactly what he’s doing. He’s shrewd.”

Though Zuckerberg shrugs off any competitive impulse, he was undeniably weaned in the upper crust cutthroat world. The son of a dentist and psychologist, he grew up in tony Westchester, New York, a gifted prodigy who fenced on his school team and made a bee-line for Phillips Exeter Academy, the storied boarding school. Aside from getting busted with a girl in his room after hours, he was a straight kid with a knack for code and self-assurance. After creating a custom MP3 player for a school project, he was courted by companies including MusicMatch and Microsoft, but turned down a $950,000 offer because he had other plans: Harvard. He wasn’t the only one, he says, “my mom really wanted me to go there.”

Coming from Exeter, and with an older sister who had gone to Harvard too, Zuckerberg didn’t feel intimidated when he arrived on campus in the fall of 2002. If anything, he soon felt kind of bored. The theoretical computer science courses were challenging, but far removed from the do-it-yourself hacker ethos that fueled the dot com innovations of his generation. So, back in his dorm, the Kirkland house, Zuckerberg began sniffing around online to see what he might do.

“This won’t be the last time I get sued,” Zuckerberg tells me.

It didn’t take long to find an answer. Frustration had been mounting on campus over Harvard’s delay in getting a promised campus-wide face book online. Zuckerberg, like other harried Ivy Leaguers, was hungry for a tool that could help him and other students stay in touch. The furthest the school had gotten was to store photos online for the students in each individual dorm.

Late one night in October 2003, after booting up the pictures onto his desktop, Zuckerberg got an idea, which he decided to chronicle in his blog. “The Kirkland facebook is open on my computer desktop,” he wrote, “and some of these people have pretty horrendous facebook pics. I almost want to put some of these faces next to pictures of farm animals and have people vote on which is more attractive.” Two hours later, he blogged again, “let the hacking begin.”

The result was facemash.com, a satirical, but sophisticated website that spoofed what an online facebook at Harvard might be. Like an insular hotornot.com, the site let visitors vote on which of two randomly selected students they thought was more attractive. Zuckerberg emailed a few friends, and the site quickly spread around campus – right up to the administration, who, along with many students, were outraged.

Zuckerberg was put on six months probation for violating Harvard’s computer use policy. In an apology letter excerpted in the campus paper, the Crimson, Zuckerberg wrote, “I apologize for any harm done as a result of my neglect to consider how quickly the site would spread and its consequences thereafter....”

In Zuckerberg's apartment, there’s a mattress on the floor. The shower has no curtain. The only indication that a budding dot com mogul lurks inside is the Infiniti FX35, a gift from Facebook’s first investor, PayPal CEO Peter Thiel, parked in the alley nearby.

Anticipating consequences, however, is antithetical to the hacker mind, and Zuckerberg soon stirred up trouble again. It started when he heard from a friend that three seniors in the Pforzheimer house – the Winklevoss twins, and Narendra - were looking for someone to code a community site they would later call ConnectU.

Narendra, an applied math major, guitar player, and self-described “social guy,” says he got the idea in December 2002 to create a site to bring students and alum together. “Harvard’s not exactly the most rambunctious social scene,” he notes, “Sites like Friendster and MySpace were blowing up at time, and it seemed like natural fit to do this at college level where you had quality control.”

When Zuckerberg’s name came up as a potential coder, Narendra and the Winklevoss twins recognized his name from the notorious Facemash debacle. But, to them, Zuckerberg’s ingenuity was an asset, not a liability. “It exemplified the idea that he had the idea of applying his skills beyond the classroom,” Narendra says, “The three of us see this as entrepreneurs; you have to be wiling to take on some risk when you’re starting something new.”

Zuckerberg agreed to help them in November 2003, but the trio say they quickly grew frustrated with his lack of output and frequent excuses for not hooking up. Phone calls and emails went unanswered, and, before long, they felt they found out why. On February 4, 2004, Narendra’s roommate handed him the latest issue of the Crimson and said, “Dude, you might want to check this out.”

The headline read “Facemash creator seeks new reputation with latest online project,” and the ConnectU team say they were devastated when they booted Facebook up. “There are slight nuances,” Cameron Winklevoss says, “but without a doubt it’s the same. He took our ideas, vacuumed them, and created his own thing.”

With a little sleuthing online, they arrived at a different picture of what Zuckerberg had been up to for the past three months. On January 11, three days before their last meeting with him to discuss their site, Zuckerberg registered the domain name, thefacebook.com. Yet during their meeting, they claim, he only vaguely mentioned working on a “personal” project. To them, the conclusion was obvious: Zuckerberg had been stalling them while he got his competing site off the ground, and, most crucially, online before them. “We felt like we had been strung along,” Narendra says.

Zuckerberg, however, says he himself “felt deceived,” and dismisses their plan as little more than a dating site, not a student directory like Facebook. “You’d use it find a girl with blonde hair and blue eyes,” he says. The ConnectU guys never had a written agreement with him, he adds, and Zuckerberg says they misrepresented the amount of work they expected in return. “They didn’t have their act together,” he tells me.

And, ultimately, nothing could reverse Facebook’s big bang. Within days, the site exploded from his dorm room to Harvard wide rage. Zuckerberg then, with the help of Moskovitz and another Harvard bud, Chris Hughes, took it to other Ivy League universities, and then schools around the country at large. Today, with America’s high schools and colleges networked, the Facebook staff, now more than 60 people, is beginning to link up schools outside the U.S.

Though Zuckerberg maintains his innocence in the lawsuit, he has become seasoned enough to know that cases like this often end in a settlement. And, he figures, if Harvard’s other beleaguered dropout, Bill Gates, is any indication, it’s par for the course.

“This won’t be the last time I get sued,” he says.

It’s 10 p.m. in Palo Alto, midday for the night owls at the Facebook loft, and Zuckerberg is heading to his small, one bedroom apartment for a break. He lives just a few blocks away in a modest rental that suits a monkish coder his age. In the living room, there’s just a mattress on the floor. The shower has no curtain. The only indication that a budding dot com mogul lurks inside is the sweet Infiniti FX35, a gift from Facebook’s first investor, PayPal CEO Peter Thiel, parked in the alley nearby.

Zuckerberg retreats to the tiny kitchen to boil up a pot of water for green tea. Despite the privilege he’s always known, and the tens of millions of dollars he’s inevitably facing, he’s discovering himself to be a man of simple needs. His only splurge is an electric guitar, leaning up against the wall. He has started meditating every day and, after getting off work at two or three a.m., unwinds by driving aimlessly through the streets with his radio on, hoping for Weezer.

But while he’s finding himself, he knows he’s not the same since the Facebook explosion began. “I was a shy kid and a computer dork,” he tells me, sipping his tea, “Being a CEO is as far from being a student as you can get.” But he’s learning. “Now I can look someone in the eye and say, ‘I want you to give me a half million dollars,’” he goes on For a moment, he steadies his gaze. Then he returns to his tea, and says, “I can feel myself changing.”